Overview

Japanese Cultural Revival of the Taisho Era

The Taisho period was a time of rediscovery of traditional Japanese culture. New folk songs were composed and the value of folk songs and folk performing arts was discovered. A new movement was born, intertwined with the trend of reviewing Japanese traditions in other fields. These include the folk craft movement (the birth of folk crafts), children’s songs composed for children based on Japanese sentiment, children’s stories that are literature for children, new folk songs composed with Japanese music in Western scales, new Japanese music composed on Japanese instruments, new dances choreographed in the Japanese style, and new Kabuki plays. New Japanese music composed on Japanese instruments, new dances choreographed in the Japanese style, and new Kabuki works. The value of Bon dances in various regions began to be reevaluated, leading to the discovery and preservation of folk songs and folk performing arts.

In addition, the invention and development of vinyl records, the start of radio broadcasting, and other media influences led to the popularity of the Tokyo Ondo dance. Bon dances that had never existed in Tokyo appeared in the city and spread to other areas where Bon dances had never existed.

This period

.

The company employees (salarymen) were formed, and the urban style, which is linked to the current lifestyle, was created during this period. The media also underwent major changes, such as the spread of vinyl records and the start of radio broadcasting. Politically, the second Constitutional Protectorate Movement and universal suffrage, which led to democracy, took place. After the Great Kanto Earthquake, the country entered an era of depression and political instability around the world, followed by a period of rural poverty and other unrest. Culturally, there was a shift from the open-minded and stylish Taisho Romanticism and Showa Modernity to erotic nonsense.

1910s-20s: Taisho Democracy

1923 Great Kanto Earthquake

March 1925 First radio broadcast

1929 Great Depression

1931 Manchurian Incident, Showa Depression

1936 The 2.26 Incident

Basic Information

Population: Approximately 55 million

Attribute type: Increased equality (realization of universal suffrage)

Longevity: about 50 years old

Famine and disaster conditions: Bad harvest every few years (especially in Tohoku Region), Great Kanto Earthquake

Media of transmission: In addition to written media, mass media appeared via radio

Territorial system: Individuals and landowners holding land

Common people’s clothing: Western clothing increased.

Food of the common people: Barley rice as the main dish, Western food begins to be adopted.

Housing for the common people: Wooden Japanese houses, large families

Entertainment opportunities for the common people: Movies were the main source of entertainment. Local dances with new folk songs also developed. Bon dances in rural areas maintained their vitality as a meeting place.

Bon Dancing: Events of the time

.

The Birth of New Folk Songs

In the course of the revival of Japanese culture, “new folk songs,” newly composed in the style of folk songs, appeared. Among these, those that incorporated the characteristics of each region in their verses appeared.

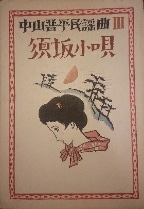

Suzaka kouta, composed by lyricist Ujo Noguchi and composer Shimpei Nakayama, was the first of the new local folk songs.

Ujo Noguchi and Shimpei Nakayama

In 1919 Ujo Noguchi </a and Noguchi Ujo and Nakayama Shinpei</strong went on a folk song trip to Mito, O-arai, etc. He appreciated Iso-bushi and other folk songs. Around this time, “Sendou-kouta (Kare-susuki)” was created. The first new folk song, “Suzaka kouta” was completed in 1923. This new folk song was not only sung but also choreographed, and the choreographer was Shizue Fujima (Shizuki Fujikage). Fujima, a native geiko, was a leader of the new dance form. She was a member of the cutting edge at the time.

Yumeji Takehisa wrote the cover of the Sheet music of Suzaka kouta (owned by Shonan Bon Dance Study Group)

About New Folk Songs

The following are some of the characteristics of the new folk songs.

Poetry: Incorporating local characteristics and local specialties

Music: Pentatonic minor scale without “le” and “so,” and without “yona

Yo=4, Na=7, Racidomifara, without 4 and 7

Choreography based on Japanese dance

By 1945, 102 Victor and 114 Columbia new folk songs had been released.

Reference: [Paper] “The Creation and Influence of Tokyo Ondo – Ondo’s Media Effect -” Yoshinori Osakabe”

Tokyo Ondo

Tokyo Ondo, a representative of new folk songs, was composed by Shinpei Nakayama with lyrics by Yaso Saijo. The original song was “Marunouchi Ondo” composed in 1932, and Kafu Nagai’s “Bokuto Kitan” describes that it was held in Hibiya Park, using yukata (summer kimono) as a ticket. In 1933, the lyrics were partially changed to “Tokyo Ondo” and the song became an explosive hit, sung by Katsutaro Kouta and Issei Mishima. It was choreographed by Hanayagi Sumi, a shinbuyo dancer. This ondo became an explosive hit and created a whirlwind that engulfed the entire country.

There were several factors that contributed to the success of Tokyo Ondo.

Tokyo’s development brought an influx of people from the countryside. Tokyo became a place where people could look back on the Bon Odori dance with nostalgia. (It is important to note that there was a big difference between urban and regional customs. There was no Bon Dance in Tokyo, but it still had strong influence in the rural area)

The strategy that we now know as “media mix” was successful. The Marunouchi Ondo was a collaboration with Shiroki-ya’s yukata. The Tokyo Ondo was promoted by holding competitions in the order starting from Shiba Park, and gramophones were used to set up competitions and courses, including those in regional areas. In addition, a film “Tokyo Ondo” directed by Houtei Nomura was produced.

Reference: Hajime Oishi, “Nippon Dai Ondo Jidai

Shinpei Nakayama’s favorite piano. He also used it to compose the Tokyo Ondo. (Nakayama Shinpei Memorial Museum in Atami City)

Representative Members of the New Folk Songs

Lyricist

Ujo Noguchi

Yaso Saijo</a >

Hakushu Kitahara, etc.

Composers

Shinpei Nakayama</strong >etc.

Singers

Katsutaro Kouta, etc.

Choreography

Shizuki Fujikage.

Sumi Hanayagi</strong >

etc.

Development of vinyl records

The phonograph/record began to be widely used in the Taisho era (1912-1926), and this led to the development of Bon Odori, which could only be performed by live singing, through the use of recording technology. Early records cataloged slang songs along with speech collections, shoka, opera, naniwabushi, kouta, gidayu, and others.

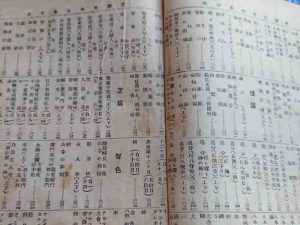

Nipponohon’s gramophone record catalog. Includes an entry of “Riyo(slang song)” (in the collection of the Shonan Bon Dance Study Group)

Start of radio broadcasting

In 1925, the Tokyo Broadcasting Station (now NHK Radio) began broadcasting. The base station was located in Atagoyama, Tokyo.

Min-yo(folk song) program by Kasho Machida started from the tentative broadcast. There was a big reaction.

Atagoyama in Minato-ku, Tokyo, where the Tokyo Broadcasting Station was located when it opened. Today it is home to the NHK Museum of Broadcasting

Early radio receiver (At the entrance of NHK Museum of Broadcasting corner)

Folk Song Collection Activities

Machida Kasho begins efforts to preserve and note folk songs, including recording and scoring of folk songs.

Machida-shiki Shaon-ki: A commercially available shaton-ki (a gramophone with a trumpet part that records the sound when the user puts his voice into the trumpet part of the gramophone). The manufacturer went bankrupt, and Machida created his own phonograph by combining the machine with a phonograph. Machida’s recording was a tremendous effort, allowing the audience to listen to prewar local recordings of folk songs.

Machida also wrote musical scores and began to work on a “Folk Song Compendium,” which was later passed on to Tsutomu Takeuchi, who spent nearly 50 years until its completion.

The Birth of Japanese Folklore

Kunio Yanagida

1910 (Meiji 43) Tono Monogatari published

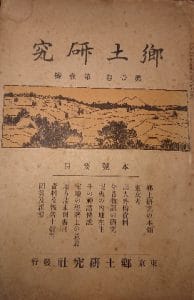

First issue of “Local Studies” published in 1913

Shinobu Orikuchi .

Founded the Society for the Study of Local History at Kokugakuin University in 1916.

Discovery of the value of Bon Dancing by folklorist

Kunio Yanagida visited the Niino Bon Dance in 1926

Kunio Yanagida visited the Niino Bon Dance and said, “This dance is a rare Bon dance with perfect characteristics, and I hope that it will be handed down to the next generation without any change in its form.

Local Studies Extra Issue (in the possession of the Shonan Bon Dance Study Group)

.

Beginning of Bon Dance Preservation Activities

Formation of the Gujo Odori Preservation Society

The Gujo Odori Preservation Society was formed in 1923.

Early folk song records

“Riyo Shu” and “Riyo Juishu” edited mainly by Tatsuyuki Takano, 1914 (Taisho 3)

Study and preservation of local dances

Start of the “Society of Folk Dances and Folk Songs” 1925: Presentation of folk dances

“Society of Folk Art”

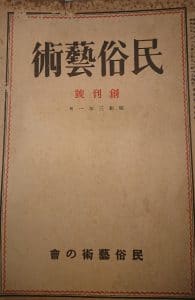

Folk Art first issue, 1928 (Collection of Shonan Bon Dance Study Group)

It is evident that a very wide range of members gathered together in a salon-like manner with great admiration for the preservation, introduction and study of the folk arts (performing arts) of the time.

They included Kunio Yanagida, Shinobu Orikuchi (folkloristics), Kyosuke Kindaichi (linguistics), Shimpei Nakayama (composer), Ujo Noguchi (lyricist), Yukichi Kodera, Kohkichi Nagata (folk arts), Hirozo Machida (Kasho Machida: composition and folk song research), who would become renowned in their respective fields in later generations. The following is a record of the founding (from the first issue of the magazine Folk Arts)

The first sponsors of the association were Yukichi Kodera and Koukichi Nagata.

The “Chronicle of the Association of Folk Arts

On July 8, 1927, the first meeting was held to discuss the policy of the association. In attendance were Kunio Yanagida, Wajiro Kon, Gakudo Yamazaki, Kotaro Hayakawa, Kyosuke Kindaichi, Taiji Shimizu, Tadakazu Hidaka, Hirozo Machida, Shimpei Nakayama, Moriko Fujisawa, Chikatada Kurata, Kenichiro Kamimori, Kyozo Takagi, Aidan Ozawa, Koukichi Nagata, and Yokichi Kodera. They discussed the name of the association, the subject matter of the research, appropriate methods, publication of materials, and other issues. It was also decided that the Association would hold a discussion meeting at any time to present and discuss its research, conduct on-site research at every opportunity, and publish pamphlets and other materials obtained by the Association, but that the actual items collected or donated by the Association would be deposited in the name of the Association in the Theatre Museum at Waseda University. The two members, Nagata and Kodera, were appointed as caretakers. The term of the caretaker was one year.

For three days from July 14, the Tokyo Broadcasting Station broadcast Bon Odori outside the home. Since two members, Mr. Hirozo Machida and Mr. Teiichi Nakaki, were related to the broadcasting station, they were especially accommodated and many members watched the live broadcasts night after night.

~The following is an abbreviated version of the report.

September 9. The first discussion meeting was held. Attendees included Ujo Noguchi, Tatsujiro Kumagai, Chikatada Kurata, Takeo Sato, Shimpei Nakayama, Kotaro Hayakawa, Hiromi Kitano, Yoshiro Haneda, Kunio Yanagida, and Yukichi Kodera. They exchanged talks on Bon Odori. Mainly, they discussed the primitive content and form of Bon Odori.

~November 12.

November 12. The third meeting. Attended by Orikuchi, Yanagida, Yamazaki, Kindaichi, Kitano, Hayakawa, Nakaki, Kamimori, Nishikakui, Nagata, and Kodera. Mr. Orikuchi gave a four-hour presentation on the “Establishment of Oh” and the rest of the meeting was devoted to discussion as usual. The meeting then moved on to the discussion of the issue of “Folk Art,” the official magazine of the association, which had been planned since a few days ago. At the same time, it was also decided to hold the first Folk Art Pictures Exhibition there in January 1928, in cooperation with Mitsukoshi Drapery Shop.

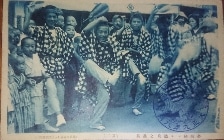

Bon Dancing as Postcards in the Taisho Era

In the Taisho period, Bon Dancing was used for postcards, indicating that it was recognized as a specialty along with the momentum to review Bon Dancing. The following postcards are thought to date back to around 1921, based on the format and postmark of the postcards. The regions vary. Some are also industrial.

Bon Dance in Toyobo Nagoya (by Niigata Work Women) () (Picture postcard: Collection of the Shonan Bon Dance Study Group)

Bon Dance of Niigata Geigi (Picture postcard: Shonan Bon Dance) (Collection of the Shonan Bon Dance Study Group)

Bon Dancing in Tokushima (Postcard from the collection of the Shonan Bon Dance

Study Group)

Bon Dance in Hirosaki (Picture postcard: Collection of Shonan Bon Dance Study Group )

Bon dance brought overseas by Japanese immigrants

Immigration to Hawaii began in 1885. At that time, it was the Kingdom of Hawaii, which became a U.S. state in 1898.

After 1908, immigration became restricted. Members of these Japanese immigrants brought Japanese culture to the area. For example, they brought with them folk customs, such as the kappa in Waipahu.

The Bon Odori dances of their hometowns were also performed, and these dances are still being performed today in the 21st century.

The dances that remain today are the Fukushima Ondo (Fukushima Prefecture), Iwakuni Ondo (Yamaguchi Prefecture), and Eisa (Okinawa Prefecture).

<The life of an immigrant was harsh: 10 hours of work, 26 days a month.

The first article was published in the Yamato Shimbun in 1905. It mentions Iwakuni Ondo. After that, the records of Bon Odori dance died out, and then it appeared again in 1915. Mr. Abe Shunichi’s memory from when he was 14 years old. At the Kokua (help in Hawaiian) plantation on Maui, we took a truck to Paia and Wailuku during Bon Festival and danced. We danced like crazy on the trucks.”

Early Bon dances are thought to have been held in the gardens where people worked and among the plantation tenements. It is thought to have made the hard plantation life bearable and strengthened kinship.

Later, Bon dances were held in temple courtyards.

As the weekends became vacations in the Western style, weekend dances took root for ease of participation.

Bon Dance in Hawaii was danced according to those which somebody memorized in Japan. In the 30s, new music, “Ondo,” was introduced from Japan

Theater promoters began holding contests, eventually offering prize money. At the end of the contest, the audience was invited to dance with the contestants.

The dance became commercial and non-faithful, and the same was true in Japan at the same time.

With the Europeanization policy, traditional Bon Odori was modified and modern dances were expanded with commercialism.

The Nisei were not religious, and the religious aspect of Bon Odori was diminished.

For the Nisei, Bon Odori was a departure from the American style of dance. The swaying of the body to Fukushima Ondo and the clapping of hands together helped to make the summer evenings more comfortable. Dancing in the stifling, crowded dance halls was more of a struggle than a pleasure….

Bon Odori became the center of entertainment for the young Nikkei community and was a fun event where friends met unexpectedly, romances were formed, and marriages were formed.

History of Bon Dance

- 0-1 The History of Uraabon

- 0-2 Ancient Japanese customs of the common people (not documented)

- 0-3 Late Heian Period, just before the birth of Bon Dancing

- 1.Kamakura Period Birth of Dancing Nembutsu

- 10.Heisei Reiwa: From Stagnation to the Birth of a New Axis

- 2.Birth of Bon no Furyu Odori (Bon Dance) in the mid-Muromachi Period

- 3.Late Muromachi – Sengoku – Azuchi-Momoyama Rise of Fuuryu Odori and Regional Expansion

- 4.Early Edo Period Establishment of Bon Dancing

- 5.Mid to Late Edo Period Bon Dancing takes root and matures

- 6.Meiji: A Turning Point for Bon Dancing

- 7.Taisho Era – Early Showa Era Revival of Bon Dancing

- 8.Before and After the War Wartime Response, Suspension and Resumption

- 9.Late mid-Showa period Nationwide expansion of Ondo and Minyo (folk songs)